She always knew it would come to this. A screaming horde of bucknaked smutcrazed rapists banging on her glass ticket kiosk. She crossed herself and with a single prayer commended her soul to the Lord’s Everafter and consigned her flesh to the Devil’s own Here and Now.

—Seth Morgan, “Street Court,” San Francisco Noir 2

Your neighborhood isn’t as lame as you think. When you move, the parts that once bothered you will follow you like a wet little dog with a boombox strapped to its back playing a mixtape from your youth, banging on your glass kiosk, returning home only to sleep; when you go back to visit, their emptiness will appear sensual, the dumb details ripe. And the parts you thought you loved? Those will evaporate, but then they will return early in the morning in your new hood, wetting your face amid a fanfare of street cleaning. Forget about what you think is sad. Your new neighborhood will reach for this old intimacy and fail. It will never know how good it was.

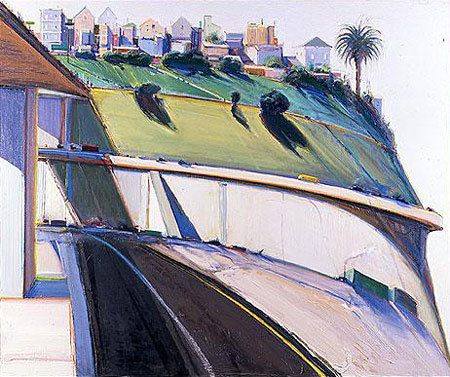

It might only be like this in the city of fog. Despite a selfish aversion to vertical growth, San Francisco’s neighborhoods share a unique sort of density. They have a buzz without a buzz. It’s not surprising, then, that the overpasses and snakeskin urban grids of boxy dwellings and smooched Victorians, the repetitive, intimate touch with which we’ve coated these hills, came to be more of Gabriele Basilico’s focus than originally planned when the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art invited the Italian photographer to come to the Bay Area and take pictures of Silicon Valley in 2007. Curator Sandra S. Phillips notes that Basilico was initially interested in “the way the freeways connect San Francisco to the peninsula.” He had never been here. Looking at maps from his home in Italy, he saw first our constant migrations, and he did end up capturing this cycle with markedly subdued shots of Highway 101, but the built environment he found along the road, from telephone poles and newspaper kiosks to Potrero Hill’s structured lilt and the simple words “Bay Bridge,” posture in his pictures with a casual anxiety that would make any startup founder proud. Basilico makes notes about how we flee ourselves, providing an urban counterpart to Candida Höfer’s lush studies of formalism. He brought to our peninsula a genius for perfectly lit architectural scenes, a second sense for resurrected cartography, and, as he told Filippo Maggia at the time, an interest in how an architecture given life by “an industrial culture…has imposed a modern image on the city;” we gave him a city of valleys emerging, a sky that is never quite decided.

It might only be like this in the city of fog. Despite a selfish aversion to vertical growth, San Francisco’s neighborhoods share a unique sort of density. They have a buzz without a buzz. It’s not surprising, then, that the overpasses and snakeskin urban grids of boxy dwellings and smooched Victorians, the repetitive, intimate touch with which we’ve coated these hills, came to be more of Gabriele Basilico’s focus than originally planned when the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art invited the Italian photographer to come to the Bay Area and take pictures of Silicon Valley in 2007. Curator Sandra S. Phillips notes that Basilico was initially interested in “the way the freeways connect San Francisco to the peninsula.” He had never been here. Looking at maps from his home in Italy, he saw first our constant migrations, and he did end up capturing this cycle with markedly subdued shots of Highway 101, but the built environment he found along the road, from telephone poles and newspaper kiosks to Potrero Hill’s structured lilt and the simple words “Bay Bridge,” posture in his pictures with a casual anxiety that would make any startup founder proud. Basilico makes notes about how we flee ourselves, providing an urban counterpart to Candida Höfer’s lush studies of formalism. He brought to our peninsula a genius for perfectly lit architectural scenes, a second sense for resurrected cartography, and, as he told Filippo Maggia at the time, an interest in how an architecture given life by “an industrial culture…has imposed a modern image on the city;” we gave him a city of valleys emerging, a sky that is never quite decided.

Like a Wim Wenders film, Basilico’s photos make you question what is ironic and what is just pathetic. Look long enough and you question yourself in the same way, ravaging the images on—not just of—your city. In fact, if it weren’t for Basilico, I might still have panic attacks on a regular basis. I want to explain how the pictures, which showed at SFMOMA a year ago and are now collected in the stunning Gabriele Basilico, Silicon Valley, 07, helped me shed a certain skin of panic. It has to do with cars, or with pictures of cars, but to get there we need to start with neighborhoods, San Francisco neighborhoods, where cars live an unstable existence.

Basilico’s scenes plea for recognition. The San Francisco Noir fiction anthologies (and the Nathaniel Rich film book of the same name) capture what it’s like to make this plea while living in a film-like San Francisco, which is funny since they depict activities that most of us will never engage in, at least not to the same extent. As editor Peter Maravelis writes in his driven intro to the recently released San Francisco Noir 2: The Classics, noir is “the language of politics without ideology.”

Basilico’s scenes plea for recognition. The San Francisco Noir fiction anthologies (and the Nathaniel Rich film book of the same name) capture what it’s like to make this plea while living in a film-like San Francisco, which is funny since they depict activities that most of us will never engage in, at least not to the same extent. As editor Peter Maravelis writes in his driven intro to the recently released San Francisco Noir 2: The Classics, noir is “the language of politics without ideology.”

The city has long provided a chance for this freedom to play out intimately. As in the first volume, there is one story per neighborhood, each with its own visual politics. Take the strongest character in “Street Court,” here representing the Outer Mission. The story is an excerpt from convict Seth Morgan‘s only novel, Homeboy (1990). The character is Nadine Ackley. She holds the anthology together. She would, I think, be at home in Basilico’s pictures, where the sky is an afterthought. She works at a movie house called the Kama Sutra, but her proximity to desire has not turned reality into a skin-tight interaction. Instead, it has all become a picture of a picture:

This nippy evening a copy of People magazine lay open on her lap. With her customary seamless blend of outrage and astonishment, she read between ticket sales the perky paeans to people who feasted at the same groaning boards of life where she starved. From time to time she inadvertently touched the photographs as though feeling for the substance behind the designer sportswear, capped teeth, and flashbulb eyes.

Later, when she resigns herself in her “glass ticket kiosk” to the “Devil’s own Here and Now,” you can see her touching the pages of People, curating, for a moment, her life. Publishers Weekly quipped that Homeboy is “marred by a highly derivative thriller plot, with characters…all tending to talk the same combination of hipster slang and B-movie cliches.” Sorry, PW, but that’s how people talk to themselves.

Spanning from 1889 (Ambrose Bierce’s high-stakes gentlemanly North Beach romp, “A Watcher by the Dead”) to the present (Craig Clevenger‘s “The Numbers Game,” where the Outer Sunset is said to be a “ghost town”), the dialogue-based stories in San Francisco Noir 2 are consistent in showing how the things we say are manifestations of a constructed environment that always includes both home and wasteland. Characters have their own rhythms, sure, but as we move toward the present and Industrialism (call it by its name or call it the feces of sprawl) breathes more and more intimately through them, even the (intentionally?) boring stories—Janet Dawson’s “Invisible Time” and William T. Vollman’s “The Woman Who Laughed”—spark a sense of controlled illness, what Maravelis in his smart introduction calls an ongoing “flowering of tragedy.” Despite the characters’ efforts at deflowering tragedy, they usually go home alone. Screw The Truman Show and its silly individualism, what’s frightening about the doppelgangers and half-criminals in safe houses here is not that they might all be you or even be against you, but that they might all be someone else.

Spanning from 1889 (Ambrose Bierce’s high-stakes gentlemanly North Beach romp, “A Watcher by the Dead”) to the present (Craig Clevenger‘s “The Numbers Game,” where the Outer Sunset is said to be a “ghost town”), the dialogue-based stories in San Francisco Noir 2 are consistent in showing how the things we say are manifestations of a constructed environment that always includes both home and wasteland. Characters have their own rhythms, sure, but as we move toward the present and Industrialism (call it by its name or call it the feces of sprawl) breathes more and more intimately through them, even the (intentionally?) boring stories—Janet Dawson’s “Invisible Time” and William T. Vollman’s “The Woman Who Laughed”—spark a sense of controlled illness, what Maravelis in his smart introduction calls an ongoing “flowering of tragedy.” Despite the characters’ efforts at deflowering tragedy, they usually go home alone. Screw The Truman Show and its silly individualism, what’s frightening about the doppelgangers and half-criminals in safe houses here is not that they might all be you or even be against you, but that they might all be someone else.![Basilico, San Jose [Redwood City], 2007](http://bp3.blogger.com/_023w4hdG0iI/R-NXBQ9ZlSI/AAAAAAAAFJg/QaFjxOIt-R8/s400/11_Basilico_RedwoodCity2.jpg)

Which is not to say that the San Francisco Noir books lack a sense of humor. Au contraire. In the new anthology, the obvious delight in language and psychological extremity that was present in the first volume is heightened by historical perspective. In the first book, I was especially fond of Kate Braverman‘s “The Neutral Zone,” where the author of Lithium for Medea writes about two old friends who live in different social spheres, meeting up at Fisherman’s Wharf, drinking in a world haunted by “invisible origami,” wondering what to do:

“We could get a tattoo,” Clarissa proposes. “Our names together in a heart.”

“A tattoo?” Zoë repeats, delighted. “Won’t it be painful and dangerous? The possibility of AIDS and infection?”

“But you love needles.” Clarissa is annoyed. “You’re a professional junky.”

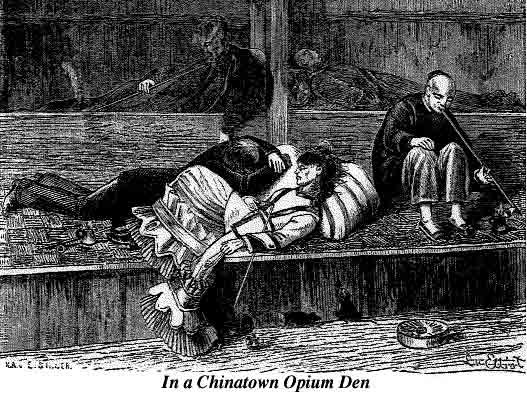

In San Francisco Noir 2, Frank Norris‘ “The Third Circle,” penned and set a century earlier, post-Gold Rush and pre-Earthquake, sees a real tattoo unexpectedly visit a finger (it’s meant to look like a ring), but it’s more frightening than witty:  “He mixed his ink in a small seashell, dipped his needle, and in ten minutes had finished the tattooing of a grotesque little insect, as much butterfly as anything else.” Despite ridiculous authorial grandstanding (“In reality,” he writes, “there are three parts of Chinatown—the part the guides show you, the part the guides don’t show you, and the part that no one ever hears of. It is with the latter part that this story has to do.”), his depiction of opium dens and half-hearted servitude is enthralling for its sense of historical anti-momentum, where the mythic parts of a neighborhood are actually pretty deadpan. When the protagonist, the tattooed, is later asked to remember how she has been taken into a drug-riddled slavery, and if she would like to escape, her main response is, “Let be! Let be! I’m dead sleepy. Can’t you see?” And later, simply, “My cigar’s gone out.”

“He mixed his ink in a small seashell, dipped his needle, and in ten minutes had finished the tattooing of a grotesque little insect, as much butterfly as anything else.” Despite ridiculous authorial grandstanding (“In reality,” he writes, “there are three parts of Chinatown—the part the guides show you, the part the guides don’t show you, and the part that no one ever hears of. It is with the latter part that this story has to do.”), his depiction of opium dens and half-hearted servitude is enthralling for its sense of historical anti-momentum, where the mythic parts of a neighborhood are actually pretty deadpan. When the protagonist, the tattooed, is later asked to remember how she has been taken into a drug-riddled slavery, and if she would like to escape, her main response is, “Let be! Let be! I’m dead sleepy. Can’t you see?” And later, simply, “My cigar’s gone out.”

Now that the stage is empty, I might as well tell you about the panic attacks. It’s actually a very simple story. They started in college and they seem to be a part of the same migraine pie I share with my mom and grandma. They’re very physical, which might surprise people who’ve never been privy to one. The worst was on 9/11, when I was volunteering on a lavender farm in Southern France and we watched the tragedy unfold on French television. My French wasn’t good enough yet to understand the high-speed newscasting, and most aggravating was how the English-speaking reporters would start to talk, only to be quickly overdubbed. I was already embarrassingly freaked out to be in a village without a single store, and the manic, un-subtitled events confounded this sense of confusion. The ensuing panic lasted for over a week, following me while I traveled north. When I came back to the Bay Area in November, I didn’t even recognize my own country. But that’s a different story.

I had always had a hard time reading about panic attacks, learning what to do, since memory is a kind of anticipation and can set off a new attack. Then one afternoon in October last year, I went for my daily walk on San Francisco’s Potrero Hill, strolling through its loping perspectives of downtown, Bernal, Twin Peaks’ multiple breasts, the Mission’s low-rise industrialism. I was trying to clear my head and get ready for a complicated trip to Europe the following week, and I was already starting to feel disassociated, panicky. I hadn’t seen the person I was always hoping to run into, but this wasn’t surprising since I knew she was never there—she had only been to an event on the hill a year ago, she doesn’t even live here. I kept looking closely at cars for some reason. With the glare I couldn’t see the drivers. Maybe that’s why. Then I walked back over the freeway and sat in my small office, gazing at the vehicles parking and scuttling on Bryant Street, and–stick with me here, just for a moment–I felt a transference of the panic to the cars. The nervous thoughts were the cars, and everything was okay because they were coming back, they weren’t driving away forever, it was just this dumb little cycle. If I’d tried to meditate on this, I would have set up a situation where the cars were the anxious thoughts, yes, but I would have had them going away forever. Au contraire, au contraire. I don’t know how long I sat there, but since that experience, I haven’t been struck with la panique, at least not about where I am. Knock on wood.

I had always had a hard time reading about panic attacks, learning what to do, since memory is a kind of anticipation and can set off a new attack. Then one afternoon in October last year, I went for my daily walk on San Francisco’s Potrero Hill, strolling through its loping perspectives of downtown, Bernal, Twin Peaks’ multiple breasts, the Mission’s low-rise industrialism. I was trying to clear my head and get ready for a complicated trip to Europe the following week, and I was already starting to feel disassociated, panicky. I hadn’t seen the person I was always hoping to run into, but this wasn’t surprising since I knew she was never there—she had only been to an event on the hill a year ago, she doesn’t even live here. I kept looking closely at cars for some reason. With the glare I couldn’t see the drivers. Maybe that’s why. Then I walked back over the freeway and sat in my small office, gazing at the vehicles parking and scuttling on Bryant Street, and–stick with me here, just for a moment–I felt a transference of the panic to the cars. The nervous thoughts were the cars, and everything was okay because they were coming back, they weren’t driving away forever, it was just this dumb little cycle. If I’d tried to meditate on this, I would have set up a situation where the cars were the anxious thoughts, yes, but I would have had them going away forever. Au contraire, au contraire. I don’t know how long I sat there, but since that experience, I haven’t been struck with la panique, at least not about where I am. Knock on wood.

Even though I think we could all use one, or something like one, I can’t afford an analyst. The closest thing I have is a combination of Hanif Kureishi’s Something to Tell You (a fiction) and George Makari’s Revolution in Mind (a history). Yet I swear that when I returned to Gabriele Basilico, Silicon Valley, 07 to start working on this essay, I looked at the exquisite pictures of Highway 101 for the first time since the exhibition and realized that they had set the scene for my odd but welcome change of mind. His Bay Bridge sign pic, ripped from reality, presents the blur and clarity that we feel every day here, not only when we’re looking at that same vision and walking back home to pretend to be in therapy. Or maybe art just got me to stop looking for the right words all the time. I don’t know. I was definitely blown away by the exhibition, while others said things like, Let’s compare these to maps. But I digress. This wasn’t supposed to sound revelatory. I am not begging you to believe me. Here’s a song that captures the feeling. Remember what the possibly schizophrenic narrator of Ernest J. Gaines‘s “Christ Walked Down Market Street” says in San Francisco Noir 2: “And do you know what that means, sir, soliciting? It means looking closely into someone’s eyes, hoping that he’s Christ. Soliciting.”

The final part of a panic attack is often wondering if anything exists at all. Dumb question, I know, but what can you do? I know you have your existential gchat moments. Maybe that’s why I only believe in the smaller miracles. The smaller, the better. Seth Morgan, once Janis Joplin’s fiance, died the year Homeboy was first published. He crashed his motorcycle into a bridge in New Orleans, high on coke and booze, killing himself and his unfortunate girlfriend of the time, Suzy Levine, and forfeiting, for better or otherwise, what would have apparently been his second novel, Mambo Mephisto. Just like your neighborhood, Morgan’s writing had an obvious humor and the type of constant haze that you can only see when you leave and then return. I’d like to think that writing Homeboy offered the trust-fund misfit a little perspective, a slight salvation, if only for the moments the pen hit paper. But it might have been more like it was for Christopher Smart, the fantasic 18th-century poet who seems to have written a line of poetry a day just to stay sane after being locked up in a madhouse for “praying in public places.” He was trying to remake religious verse, and all he got was a kick in the ass.

The final part of a panic attack is often wondering if anything exists at all. Dumb question, I know, but what can you do? I know you have your existential gchat moments. Maybe that’s why I only believe in the smaller miracles. The smaller, the better. Seth Morgan, once Janis Joplin’s fiance, died the year Homeboy was first published. He crashed his motorcycle into a bridge in New Orleans, high on coke and booze, killing himself and his unfortunate girlfriend of the time, Suzy Levine, and forfeiting, for better or otherwise, what would have apparently been his second novel, Mambo Mephisto. Just like your neighborhood, Morgan’s writing had an obvious humor and the type of constant haze that you can only see when you leave and then return. I’d like to think that writing Homeboy offered the trust-fund misfit a little perspective, a slight salvation, if only for the moments the pen hit paper. But it might have been more like it was for Christopher Smart, the fantasic 18th-century poet who seems to have written a line of poetry a day just to stay sane after being locked up in a madhouse for “praying in public places.” He was trying to remake religious verse, and all he got was a kick in the ass.

2 responses

Well written Mr. Messer!

Makes me nostalgic for the Bay Area mindset, contrasting genres (photography and fiction) to try to touch on something personal (panic?).

Also makes me curious to see the work of Basilico (an outsider’s view on the City), and read the stories in San Francisco Noir 2 (perhaps more insiders’ views?). I’m left with the often stated question, who is an insider in SF? Perhaps someone who is searching for “what is ironic and what is just pathetic” and something “visually political”.

As a manifestation of her inhabitants’ collective psyche, the city’s architecture belies our fears of loneliness and loss. Her bridges reach out, connecting her to the world, but are also open wounds that bleed things like the girl who should be meeting you on Potrero Hill. When the Void weighs in on me, I resort to time travel. A car in a photograph is no longer a moving object. It no longer symbolizes the terrifying flux of a world careening towards our deaths. A doppelganger locked in prose is no longer a mortal; he has nothing to lose and nothing to fear. A neighborhood is a good place to hide from loss until you leave it. (I’m moving to your city, leaving my old neighborhood today because it’s as lame as I know it is.)

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.